Harnessing the Storm

The Panavia Tornado needs little introduction, for nearly half a century, This aircraft has filled a critical niche in NATO’s strike and reconnaissance abilities in Europe through the Cold War and beyond.

Beyond the aircraft’s military duties, the Tornado represents much more from standpoints of aeronautical, industrial and political success.

The Tornado was the first aircraft of its class and complexity to be created by a multinational consortium. Early challenges involved agreeing on the form the new aircraft would take while still being able to satisfy the differing requirements of the participating nations as well as a division of labour in building the aircraft that accurately reflected the level of participation each of the consortium’s member nations had in the overall program.

The industrial and political implications of the Tornado were considerable. It was a showpiece of sorts that clearly exhibited that America did not have a monopoly on creating modern strike aircraft among western nations and that European aircraft manufacturers were capable of producing aircraft of the class that were quite competitive with contemporary American designs. While the Tornado did ultimately contain some American made avionics, this content was very limited and tightly controlled. Every effort was made to ensure the Tornado was European first and foremost.

Aeronautically, the aircraft exhibited a high degree of modular construction in all aspects as well as an unprecedented degree of automation and computerisation in many aspects of flight and operations. The aircraft’s modular nature would pay dividends in time saved during ground servicing and upgrading while the level of automation the aircraft’s computers could provide reduced aircrew workload and fatigue significantly relative to earlier aircraft types of its class.

Ultimately, in spite of all early obstacles, the Tornado was brought into existence and has won respect on a global scale.

In this entry, I will focus on the IDS (Interdictor/Strike) versions of the Tornado as I have already written a separate piece on the ADV (Air Defense Variant) of the aircraft.

Bringing Things Together

The story of the Tornado starts in August of 1967, when a working group of five nations came together with the intent of creating a multi-role aircraft to replace the American designed Lockheed F-104 Starfighter that all were using at the time. The five nations involved were: Belgium, Canada, Italy, the Netherlands and West Germany. The project was initially known as MRA75 (Multi-Role Aircraft for 1975).

Great Britain joined the group in 1968. The main motivation for the British to involve themselves in MRA75 was to find partner nations to further the UKVG (United Kingdom Variable Geometry) strike fighter design that had grown out of the failed AFVG (Anglo-French Variable Geometry) fighter design that had been in development between 1965 and 1967. The UKVG design was taken as a basis from which to develop the MRA75 design and where the Tornado inherited its variable geometry wings from.

An additional impetus for Great Britain to join the group was that the infamous defense white paper of 1957 had thrown all aspects of the British defense industry, particularly the aviation industry, into a state of great upheaval. The effects of the white paper included government forced mergers of aviation companies and the cancellation of a number of critical defense programs. Most notable among these cancellations, in the aviation context, was that of the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) TSR.2 in 1965. The TSR.2 had been a highly ambitious project of great complexity and, consequently, very expensive from an early stage. The rising cost of the TSR.2 program is the most frequently cited reason for the cancellation of it. However, shortly after the TSR.2 cancellation the idea was proposed to replace it with a British specific version of the General Dynamics F-111 from America that was to be known as the F-111K. The F-111K would also have been very expensive and was ultimately cancelled before a single aircraft was built.

What was clear, with the financial losses incured by the cancellations of the TSR.2 and F-111K programs, was that Great Britain could no longer bear the financial load of a new strike fighter alone. If the Royal Air Force was to have their new aircraft, British industry would need to find outside partners to help.

In March of 1969, the multinational consortium was formally named Panavia Aircraft GmbH and its headquarters were placed a short distance north-west of Munich. In the same period of time, the program was renamed from MRA75 to MRCA (Multi-Role Combat Aircraft) and its general configuration had been agreed upon with single and two seat variations of the design under consideration.

The constituent companies of Panavia were MBB (later Airbus) from Germany, BAC (later BAE Systems) from Great Britain, and Aeritalia (later Alenia Aeronautica) from Italy. The workshare saw MBB and BAC taking 42.5% each with the remaining 15% going to Aeritalia. BAC would be responsible for the forward fuselage and tail sections while MBB would build the centre fuselage section and Aeritalia would build the wings.

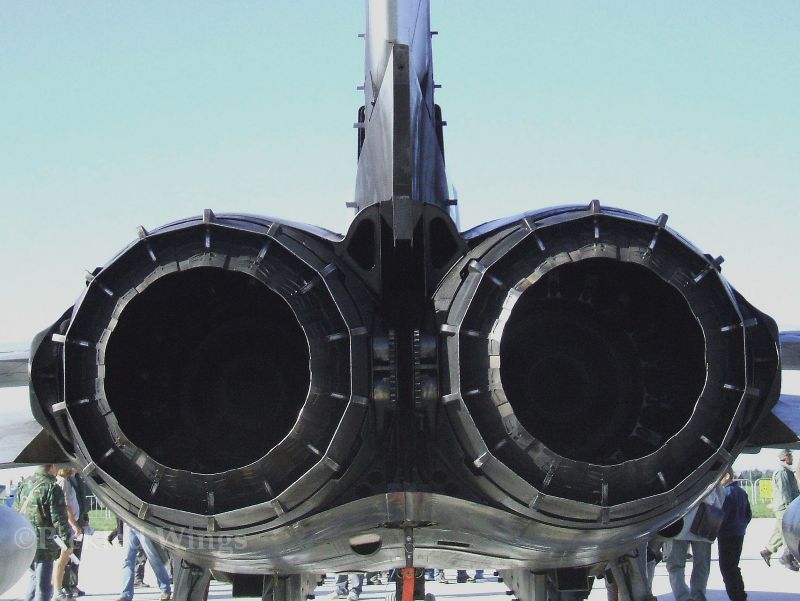

In mid 1969, a similar multinational consortium was assembled to design and build the MRCA’s engine, the RB.199. This group was named Turbo Union. As with the MRCA itself, the RB.199 engine represented a multinational defense project that was of unprecedented scale and complexity in the European industrial context.

Turbo Union was made up of MTU Aero Engines from Germany, Rolls-Royce from Great Britain and Fiat Aviazione (later Avio S.p.A.) from Italy. MTU and Rolls-Royce each took 40% of the workshare, leaving 20% for Fiat. Turbo Union headquarters were initially placed at Rolls-Royce facilities at Filton in south-west England and later relocated to the company’s main facilities near Derby in central England.

Belgium, Canada and the Netherlands had all withdrawn from the program before much was formalised with regards to workshare. Italy, Great Britain and West Germany would be the partner nations of Panavia from 1969 onward.

Into the Air

While the face of the MRCA and its makers had been largely cemented by 1970, there was still work to be done before the first prototype would take to the air four years later.

The RB.199 was run for the first time on a stationary test bed in September of 1971 and a month later a radar system from Texas Instruments was selected for the aircraft.

Construction of the first MRCA prototype commenced in November of 1972 while the RB.199 was run for the first time in the air, using an Avro Vulcan bomber as a test bed, in April of 1973.

The first complete MRCA prototype was rolled out of its hangar in Manching, West Germany in April of 1974 and flew for the first time in August of the same year.

1974 also saw the MRCA officially given the name “Tornado”. While there had been some debate over what name the aircraft would be given, Tornado was ultimately chosen as the word meant the same thing in all three languages of the Panavia partner nations. From a British point of view, it was also in keeping with the Royal Air Force tradition of naming fighter aircraft after extreme meteorological phenomena.

Extensive flight testing filled out the rest of the 1970s for Panavia and the Tornado. While the flight testing phase was not without incident, the third and fifth prototypes were lost in landing accidents while the eighth prototype and its crew were lost when the aircraft crashed into the Irish Sea in 1979, it was an overall success.

Into Uniform

The first Tornado flying unit was the Tri-national Tornado Training Establishment (TTTE), which was formed between 1980 and 1981 at the Royal Air Force station at Cottesmore in the East Midlands region of England. As the name of the unit suggests, crew training on the Tornado was as balanced multinationally as any other aspect of the machine.

Until its disbandment in 1999, the TTTE was responsible for initial aspects of Tornado training. Ever increasing differences between the operational specifications and systems fits of the various user nations’ Tornado fleets was the major contributor to the unit’s disbandment as it made more sense for the user nations to create their own training units geared to their individual Tornado fleets.

In 1981, advanced schools for weapons training on the aircraft were established in the UK an West Germany.

1982 saw the first three RAF Tornado squadrons form, all of which had been former Avro Vulcan bomber units. That same year saw the first West German navy Tornado squadron established, itself a former Lockheed F-104 Starfighter user.

The first Luftwaffe and Italian air force Tornado units were established in 1984

The first Tornado units of the Royal Saudi Air Force were activated in 1986

Between 1995 and 2005, the German navy eventually was relieved of its fast jet force and associated roles with its Tornado fleet being absorbed into Luftwaffe stocks.

The Tornado in Action

In its years of service, the Tornado has been an invaluable asset to NATO through the latter stages of the Cold War and beyond.

Through the mid to late 1980s and most of the 1990s, the Royal Air Force maintained a total of eight Tornado squadrons at a high level of combat readiness at bases in Germany.

As with most combat aircraft of its generation, the Tornado got its first taste of true combat during the Persian Gulf War that lasted from 1990 to 1991. Tornado units from Italy, the UK and Saudi Arabia took part in the conflict.

In the wake of the 1990-1991 Gulf War, Royal Air Force Tornado units stayed in the region as part of Operation Provide Comfort which ran from 1991 to 1996 with the intent to protect Kurdish populations in northern Iraq and ensure humanitarian aid to them.

RAF Tornado units also participated in Operation Southern Watch which ran from 1992 to 2003 to enforce the Iraqi no-fly zone established after the war that extended from the 32nd parallel southward.

In December of 1998, RAF Tornados were used in the highly controversial Operation Desert Fox. The operation was a four day bombing campaign against targets in Iraq.

Luftwaffe Tornados provided valuable reconnaissance during the Bosnian War which lasted from 1992 to 1995. This was particularly significant as it marked the first time German forces had engaged in combat action since the Second World War.

Tornados from Germany, Italy and the UK all particpated in the Kosovo War which lasted from 1998 to 1999. The aircraft carried out bombing and reconnaissance as well as the suppression of ground based anti-aircraft sites.

RAF Tornados were used extensively during Operation Telic, The British contribution to the 2003 invasion of Iraq and subsequent occupation of the country until 2011.

British, German and Italian Tornados all, at one time or another, took part in the 2001 to 2014 NATO led security mission in Afghanistan to combat Islamic State (IS) militant cells.

British and Italian Tornados took part in the 2011 military intervention in Lybia which resulted in the overthrow of the Gaddafi regime.

Since 2015, Saudi Arabian Tornados have been used in the ongoing Saudi led multinational intervention against Islamic Houthi insurgence in Yemen.

The Tornado Strike Family

The IDS (Interdictor/Strike) version of the Tornado encompasses seven variants.

Tornado IDS:

The baseline IDS version of the Tornado is used by both Germany and Italy for strike and reconnaissance duties.

Tornado Gr.1 and Gr.1A:

The Gr.1 was the initial British version of the IDS. Equiped with British specific avionics and systems, it could be differentiated from other IDS variants by the presence of a laser targeting pod to the right of the nose landing gear as well as differences in antenna fit and the type of pods carried on the outboard wing pylons for the aircraft’s self defense.

The Gr.1A was the RAF’s reconnaissance optimised version of the Tornado. It could be distinguished from the Gr.1 by windows for the infrared based reconnaissance gear on either side of the forward fuselage and the absence of the two 27mm nose cannons that were standard armament for early IDS versions. The cannons had to be removed to make room for the reconnaissance gear.

When Saudi Arabia decided to purchase the Tornado, it was Gr.1 and Gr.1A versions they opted for.

Tornado Gr.1B:

This was a rare and short lived Tornado variant. The Gr.1B was a maritime strike optimised version intended to replace the RAF’s aging fleet of Blackburn Buccaneer aircraft. A total of 26 Gr.1 aircraft were converted to the GR.1B standard.

Two main problems resulted in the Gr.1B having a relatively short service life: early troubles in getting the aircraft to work well with the Sea Eagle anti-ship missile it was equiped with and an unrefueled range that was inadequate to effectively cover the UK’s large maritime patrol and strike zone.

Tornado Gr.4 and Gr.4A

These variants of the Tornado were the result of a mid-life upgrade program for the Gr.1 and Gr.1A that saw a total of nearly 150 RAF Tornados upgraded to Gr.4 or Gr.4A standard between 1996 and 2003.

The most visible difference between the Gr.1/Gr.1A and Gr.4/Gr.4A is the addition of an infrared targeting pod on the left side of the nose landing gear. In the case of the Gr.1, the left side nose cannon was removed to make room for the pod’s systems.

The difference between the Gr.1A and Gr.4A was more one of a change in the aircraft’s mission profile. The Gr.1A and its built in infrared reconnaissance system were optimised for low altitude operations. The conversion to Gr.4A saw the aircraft’s mission profile changed to one of medium altitude and the built in reconnaissance system replaced by external pod based systems.

Tornado ECR:

This version of the Tornado debuted in 1990 and is used by Germany and Italy for electronic combat and reconnaissance.

The ECR specialises in the SEAD (Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses) mission, a highly risky mission which requires specially equiped aircraft to fly into an area ahead of the main strike group to detect and destroy tracking radars of hostile ground based anti-aircraft gun and missile systems.

In order to accommodate the required gear to carry out the SEAD mission, both nose cannons had to be removed in creating the ECR.

There are a few differences between the German and Italian ECR Tornados. The German aircraft have built in reconnaissance systems as well as external pod based ones while the Italian ECRs rely only on pod based systems.

The German ECR fleet was built factory fresh while the Italian ECRs were converted from existing IDS stocks. Additionally, the German ECRs have slightly more powerful engines than the Italian ones.

The Tornado Today

After more than four decades of solid service, the curtain is slowly falling on the Tornado.

The last of the Royal Air Force’s Tornado fleet was retired in March of 2019 while Saudi Tornado force retirement is set for sometime in the 2020s.

Germany and Italy have both forecast the complete retirement of their Tornado fleets for the 2025 to 2030 timeframe.

If you’re in the right place at the right time, there is still a chance to see a Tornado in “living” form.

Happily, a good number of Tornados have found their way into museums across Europe and Saudi Arabia. At least two Tornados are on display at museums in America.

Learning More

A good first stop for Tornado information on the internet is the Panavia home page.

In book form, I can heartily recommend Michael Napier’s “Tornado Over the Tigris”. The book is a memoir of Mr. Napier’s 13 years as a fast jet pilot in the RAF.

“An Officer, Not a Gentleman” by Mandy Hickson is a memoir of the Royal Air Force’s second ever female fast jet pilot. While the book is not exclusively about the Tornado, the author spent three years of her RAF career flying the Tornado Gr.4 and this book gives some good insights into Tornado operations and life in an RAF Tornado squadron.

I can also recommend “Tornado Boys”, a collection of stories told by those associated with the aircraft in the RAF and compiled by Ian Hall.

“Panavia Tornado” by Bill Gunston, while long out of print, covers the pre-service development of the aircraft very well.